I think it’s Thursday. I know it’s still November. But if my GP were to do one of those tests to assess my cognition right now, I’d have trouble with the year, and where I am, more specifically the international boundaries of our nation. Let me explain.

My routine is so shaken up, I wake up not knowing what day it is.

Each week of this lilac month has had not one but two important events, in not one but two important areas of my life, that I’ve played a big role in, if not outright organised.

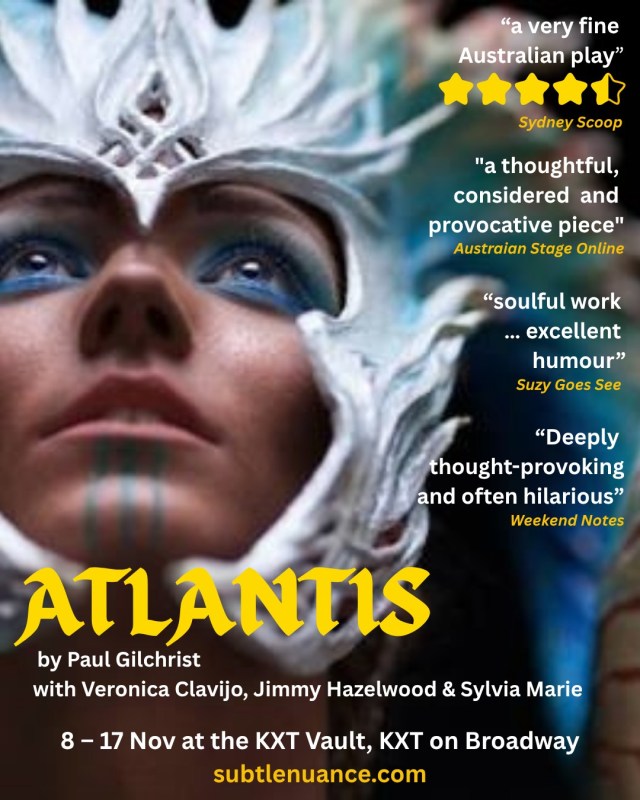

At work we’ve had a short film competition culminating in an Award night, and a look back public talk, 50 years on, commemorating the 1975 Dismissal. In my theatre world, subtlenuance has just produced Atlantis by Paul Gilchrist at KXT on Broadway, to great acclaim.

Broadway Sydney that is. You know that lively hub between Victoria Park and UTS. We put on the play in the Vault, a cool new space in a cool little indie theatre. Literally the basement of the old 1890s sandstone bank building the theatre is in. Our performance space was in front of the reinforced steel door that opens into a small room that holds the safe (behind a set of floor to ceiling iron bars) where the gold was kept. A vault. The production went off! And I even got to perform one night, standing in for an actor with a script. And now, we’re about to bump in our second production in the space, Stella, “A confronting comedy about being the centre of the universe” – you can buy tickets here.

The show starts just after I get back from New Zealand. Oh yes, I forgot to mention, I’m popping over to New Zealand for a few days.

Is it any wonder I don’t know what day it is?

But back to international boundaries. For some reason, all of this excitement has regressed my brain, not back to childhood as usually happens with memory loss, but back to circa 1899.

Although some days I do feel that my childhood happened in the 19th century.

Here’s an example. I was at work and hadn’t yet begun to prepare for my trip, which is a work trip, when my colleague said, “Be sure to pack a coat, it’s 16 degrees in Wellington”. This was on a 30-degree day in Sydney. So, I checked the BOM app on my phone. And then I said to my colleague, “Are you sure? This says it’s 32 degrees in Wellington.” And because I’d been stupid enough to say this out loud and in front of all my other colleagues, laughter erupted across the office and reverberated through the entire building, until one wag finally was able to choke out, “That’s Wellington NSW! You can’t look at New Zealand weather on the BOM! New Zealand is another country!”

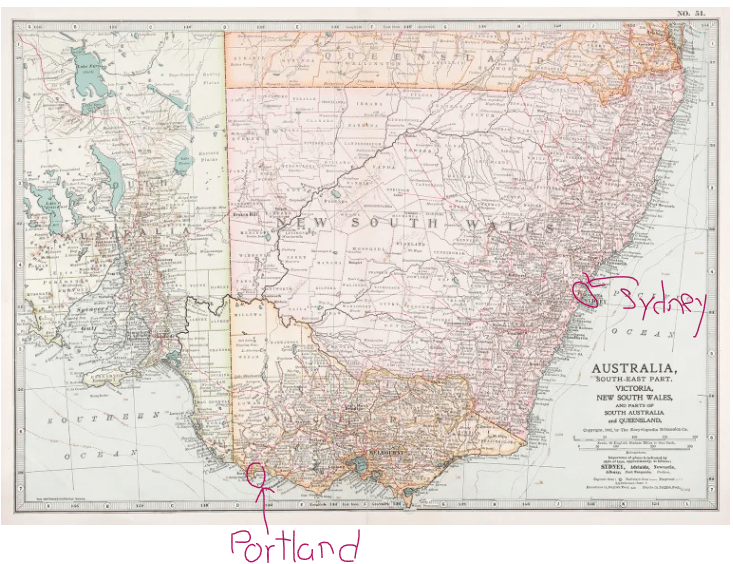

Well. That’s easy to say now but as an ex-history teacher and a civic educator, I happen to know that in the 19th century, New Zealand was invited to join the Australian Federation, and participated in the early Federation conferences. Yes, they did decline the invitation just before all the other Australian colonies took the equivalent of marriage vows before any concept of divorce existed, but the Australian Constitution still includes a clause allowing for New Zealand’s future admission*.

I didn’t say any of that out loud to my colleagues of course. I simply retreated into an internal panic in which I had flashbacks to remembered fragments of other conversations I’d had recently. Like another colleague telling me to only pack liquids in 100ml bottles. And my partner gently suggesting that booking a taxi to get me to the airport only an hour before the flight wasn’t the best idea.

Now I get it!

It’s an INTERNATIONAL flight!

Suddenly, all of the hurdles I’d need to jump over the next few days rose before me. Would my phone work there? What about money? Would my card work there? Do they even have the internet? I mean, Peter Jackson did film Lord of the Rings in New Zealand. Yes, it was because of the stunning landscape but was it also because the country is authentically Middle Earth in other ways?

Do I need a Visa? I mean we’ve let a lot of New Zealanders into Australia over the years without one but do they feel the same way about us?

Luckily, I had renewed my passport recently. I do it as a matter of course even though, as you can tell from above, I haven’t actually left the country in at least 20 years. The last time, ironically was to New Zealand. But that was the South Island. And it was in the days before the internet and mobile phones. Or close to.

I renew my passport regularly because I wasn’t born in Australia. We came here on the S.S. Ellinis from Cape Town. My parents were economic migrants and I came with them when I was 7. They became citizens at Westfields Liverpool in 1978 – you can read about that crazy event here – and my name appears on the bit of paper they gave dad as an addendum to his citizenship. And because he’s been gone for quite a while now, and that bit of paper is rather old and frayed, and because I’ve kept up with how Australia treats some classes of non-citizens, the fear of random deportation to a country I don’t even remember has kept me turning up like clockwork, once a decade, at the passport office.

But now I’m all packed and I’ve ticked off all of the little boxes on my international travel checklist. And I’ve refreshed my understanding of what is and is not geographically part of Australia. After all, I don’t want to get into any conversational hot water with any proud citizens of New Zealand. I’ll be keeping that little tit bit about Section 21 of the Australian Constitution to myself.

And so, here’s to spending the last week of November in another time zone. I look forward to waking up not knowing what day of the week it is, or where I am, and actually having a good reason for it.

Notes and attributions: * Covering clause 6 of the Constitution states New Zealand may be admitted into Australia as a state. Section 121 provides the rules on how new states would be admitted. https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/your-questions-on-notice/questions/new-zealand-is-mentioned-in-the-australian-constitution-does-that-mean-that-new-zealanders-have-the-legal-authority-to-vote

Poster_australia_NZ_1788_1911_shepherd_1923 via Wiki Commons Media

National Archives of Australia, Public domain, via Wiki Commons Media

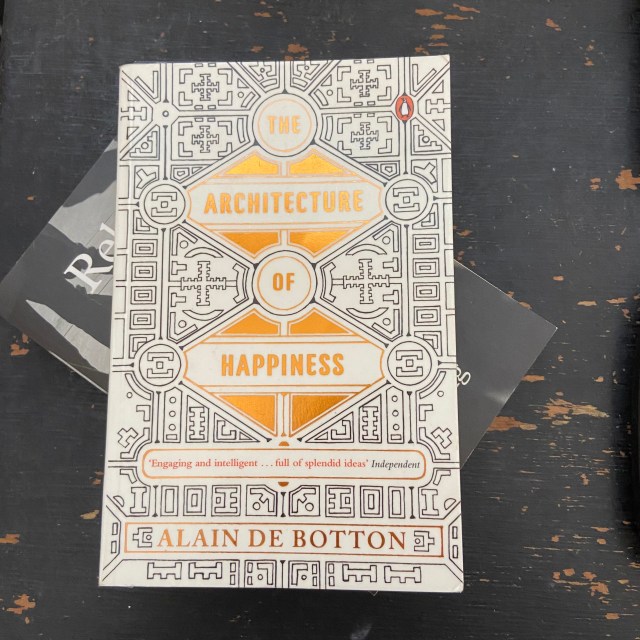

Lonely mountain by MaximKartashev – Own work, Public Domain via Wiki Commons Media

On the weekday morning in mid-January that I stepped into this foyer it was filled with crisp suits and pretty office dresses which easily matched the beauty of the space. I was carrying out my own small acts of resistance by not wearing either of these uniforms, and feeling fine about not spending my day toiling in the heights of this great tower. But I was not going to resist the nutty caramel smell coming out of the coffee machine.

On the weekday morning in mid-January that I stepped into this foyer it was filled with crisp suits and pretty office dresses which easily matched the beauty of the space. I was carrying out my own small acts of resistance by not wearing either of these uniforms, and feeling fine about not spending my day toiling in the heights of this great tower. But I was not going to resist the nutty caramel smell coming out of the coffee machine.

The next day I discovered that I’d be saving two butterflies – another caterpillar had joined its little friend for dinner. Between them they’d eaten half the lime tree overnight. I watched them for several days as they continued to feed, until the first one was almost the size of the tree itself.

The next day I discovered that I’d be saving two butterflies – another caterpillar had joined its little friend for dinner. Between them they’d eaten half the lime tree overnight. I watched them for several days as they continued to feed, until the first one was almost the size of the tree itself.