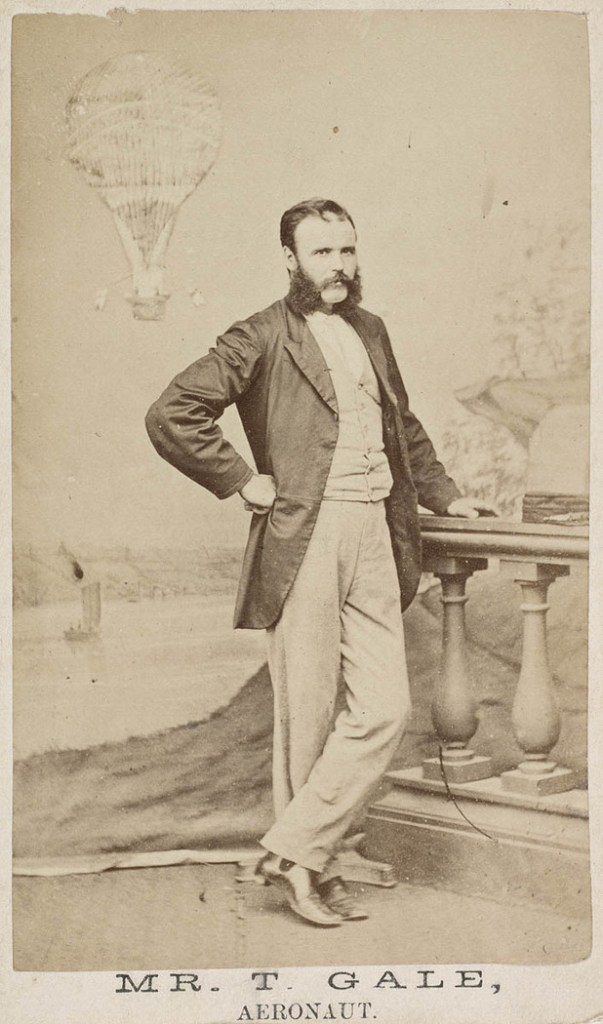

It was an overcast September afternoon in 1870 as Thomas Gale waited for his balloon to fill so that he could make good his promise to take to the skies. Gale could feel the excitement of the huge crowd around him. They were at the Intercolonial Exhibition in Prince Alfred Park, Sydney to see the famous British aeronaut, who had made over seventy balloon flights in his career.

Gale’s was not a hot air balloon, but powered by highly explosive gas, likely hydrogen. Lighter than air, but more expensive, gas got balloons off the ground more easily than air and once away, they stayed up longer. But despite his experience and outer calm, Gale was tense. His most recent attempt, only days earlier, had failed because of the weather. Now, as he watched, a shower of rain soaked the fabric of his balloon making the oiled over cotton bandages that it was constructed from a lot heavier. There was not enough gas to fill a heavier balloon and Gale knew that an enthusiastic Exhibition crowd could quickly turn into a disappointed, riotous mob.

So, he made his decision. He removed the basket from the balloon, told his no doubt disappointed passenger that he would be left behind, and for good measure, took off his wool jacket; lightening the load to ensure his balloon would fly. Accompanied by jubilant cheers, Gale jumped onto the hoop, the cables were freed, and the balloon left the ground. Lifting up into the air it caught the breeze and began its drift to the south with the balloonist clinging to the ropes as the delighted crowd watched.

His aim was to make it to Botany Bay. But suddenly, about a kilometre from the park, where the suburbs of Waterloo and Alexandria meet, the wind dropped and his airship was becalmed. When finally a southerly breeze propelled him back towards Redfern the crowds in the park saw the balloon returning and rushed to meet him where it came down. They hijacked a horse driven furniture van to transport Gale and his balloon back to Prince Alfred Park. Although disappointed, Gale was determined to continue his aeronautical experiments.

Thomas Gale’s father was also a balloon aeronaut. He crossed the Channel from England to France in 1850. That same year he attempted another daring flight. Rather than attaching a basket to his balloon, he attached himself, on the back of a horse. I have trouble imagining how this was possible. But he managed not only to take to the air but also to land successfully. However, as he touched down, his assistants released the horse and accidently let go of the balloon, with the aeronaut still attached to it. It lifted off again with Gale Senior clinging to the ropes. Although he was able to let gas out of the balloon and direct it to land, he couldn’t control the outcome. His body was found the next day near the half-inflated balloon. His newly widowed wife was left to look after their eight children. Twenty years later, his son, Thomas Gale, ascended into the skies above Prince Alfred Park. I can’t help but wonder what possessed him to also take to flying balloons knowing how his father’s adventures had ended.

In June of 1871, just short of a year after his flight from Prince Alfred Park, Thomas Gale met the woman that he would marry while preparing to take to the skies over Adelaide. To keep the gathered crowd entertained while they waited for the balloon to fully fill with gas, Gale welcomed a small group of onlookers to join him in the basket. The tether rope was loosened as far as it would go while still restraining the balloon. To the delight of the crowd and the lucky thirty or so in the basket, the balloon rose into the air. One of the passengers was Lavinia Balford. She became the first South Australian woman to ride in a balloon, albeit only sixty metres above the ground, and a little while later she married the aeronaut. They lived in Adelaide for the rest of their lives. Thomas continued his aerial adventures, taking passengers on many of his flights and inspiring other aeronauts to daring feats in the skies. He made some money, but also a lot of debt, which landed him in the Adelaide Insolvency Courts in 1879 where he was declared a bankrupt. I suppose his fate could have been worse.

About a week ago, coincidentally 153 years to the day that Thomas Gale ascended into the skies from Prince Alfred Park, I took part, along with thousands of other like minded people, in the ‘Walk For Yes’ rally. It’s route took us right past the very spot where Gale waited for his balloon to fill on that September day in 1870. When I mentioned this coincidence to my walking companion, I was reminded that there is a children’s playground in the park in which there is an elephant and a balloon. Neither of them are real. On close inspection though, you can see that the trunk of the little grey elephant is a slippery dip and the balloon is a steel climbing structure. Next to the balloon and the elephant, on its own small beach of sand, is a pretty, grey and green row boat, with the name Galatea stencilled on its stern. This was the name of Prince Alfred’s ship, and the baby elephant, named Tom, was gifted to Prince Alfred, Queen Victoria’s son, the Duke of Edinburgh, on his stopover in India. He was on his way to Sydney to attend the Great Exhibition which was held in this park. Both Prince Alfred and Tom the elephant were in the park on the same afternoon that Thomas Gale set off on his adventure across Redfern. I have wondered at the courage of the Prince, returning to Sydney so soon after an assassination attempt curtailed his first visit, but that’s another story. I have also wondered why the designers of the playground juxtaposed these stories together forever. Perhaps they represent courage in the face of adversity (The Prince). Persistence despite the odds (Thomas Gale). And hope – that our journey into the future (the boat) will be better than our unforgettable past (the elephant). Perhaps this analogy draws the bow a bit too far. But let me attempt to draw it even further.

On Saturday 14 October 2023, Australians will be asked to vote for a ‘Voice to Parliament’ for Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. For those of us who hope that the majority of Australians will vote Yes, this is a time to emulate the courage of Prince Alfred and the persistence of Thomas Gale. A time to hone our patience and hand out leaflets. A time to talk to friends, family, colleagues and strangers about the issues. A time to allay fears and remind ourselves of the many courageous acts that this country has witnessed. And when the results are revealed, I truly hope we will have landed in a more equal society. A place where Indigenous Australians no longer die ten years earlier than anyone else. A place where Aboriginal children have as much chance as the rest of us to finish high school. A place that has listened to the culture that has continuously been here for 65 000 years and in that listening can change the lives of the truly disadvantaged. Let’s vote for a future we can be proud of where every voice is heard. Let’s add a giant YES to the children’s playground next to the elephant, the boat and the balloon.

Image Credit: https://www.yes23.com.au/